12/31/2025

Learning Curves With Hybrid Growing Mixes

Dr. Brian E. Jackson

I love seedless watermelons. Among all the “hybrids” in the plant kingdom, this one is a great example of the result of crossing two (or more) things together to achieve something truly unique that often solves a problem and/or creates an opportunity (new market).

Despite being inedible, soilless substrates play their own important role in horticulture and have, like the seedless watermelon, changed our preferences, practices and decision-making process.

The supply

While the peat industry in Europe is ringing the alarm bells and warning of supply chain shortages (down 40% to 50% overall) this year due to the historically low peat extraction season in 2025 (reportedly, the lowest since 1998), we’re extremely fortunate that the situation in Canada was much better. The Canadian peat harvest in 2025 was strong overall (~400 to 450 million cu. ft.) due to better weather during the harvest months. As reported by the Canadian Sphagnum Peat Moss Association (CSPMA), peat producers are confident that they’ll meet the growing demand for the product.

Similarly, coconut coir prices have risen significantly for many growers over the past year due to unpredictable weather conditions (prolonged monsoons) in coconut production regions, the global demand surge for coir products, increased buyer competition (particularly from China) and cost inflation (energy, labor, freight, tariff threats, etc.). According to growers and coir suppliers, these and other converging pressures are expected to keep prices where they are (at best) or possibly higher in the year(s) ahead.

It should be noted that price increases and product availability aren’t necessarily universal and can vary based on the buyer, how much they purchase, long-standing relationships with their suppliers, etc. One thing that we as an industry have learned is the annual surplus or deficits of substrate materials creates long-term uncertainty in supply chain security.

The fluctuation in substrate supply from year to year in conjunction with some peat reduction efforts around the world has brought global scientists and industry leaders together, now more than ever, to collectively assess the current limitations on substrate availability and to identify the main barriers to future substrate development. While attending the ISHS Growing Media Symposium in Germany last September (2025), I participated in a workshop on “Emerging Limitations to Growing Media Security (2025–2035),” which involved experts from academia, industry, non-profit organizations and policymakers, among others.

The workshop, coordinated and led by Dr. Beatrix Alsanius from Sweden, was based on six overarching concepts related to the future of growing media and soilless crop cultivation: 1) climate and environmental stressors; 2) political and regulatory constraints; 3) market and economic factors; 4) resource scarcity and supply-chain fragility; 5) quality, performance and technical challenges; and 6) knowledge, innovation and transition gaps. Participants were tasked with identifying and ranking systemic risks and transformation needs relating to the use and access of substrates in the future.

A summary of the discussions from the workshop indicated that, among other things, geopolitical uncertainties, limited market access to peat alternatives and the lack of investment in the future of soilless substrates all created “barriers to transition” to novel substrate adoption for many users (growers). Many of these topics/issues are realities for us here in the U.S., as well.

To fix a problem, you have to first truly understand it. Fortunately, in recent years, funding in the U.S. has increased to help us prepare for our future substrate/growing needs. Agencies including the USDA, The American Floral Endowment, The Horticulture Research Institute and numerous others are currently supporting many efforts, some of which are highlighted in this article.

To fix a problem, you have to first truly understand it. Fortunately, in recent years, funding in the U.S. has increased to help us prepare for our future substrate/growing needs. Agencies including the USDA, The American Floral Endowment, The Horticulture Research Institute and numerous others are currently supporting many efforts, some of which are highlighted in this article.

The options

Traditionally, professional substrates in the U.S. contained peat plus one other component/material (mainly perlite). Many substrate products today often contain multiple components blended at various ratios. The benefit of this can be a lessened reliance on sole-source materials, but it can also complicate the reproducibility and quality control/assurance of mixes, as well as their management in crop production.

Some domestic substrate components that are currently on the market (available in professional or retail mixes) include engineered wood fibers mostly derived from native conifer species, but some newer ones made from hardwood trees are being trialed and adopted by growers (Figure 1A & B).

Bark, a long-time staple substrate of the nursery industry, is now used a lot in peat-based mixes or as stand-alone substrates, and it can be milled, double-processed or extruded to make unique components better suited for greenhouse and specialty substrates (Figure 1D & E).

On the market for many years, Pittmoss (Figure 1G) is an example of a non-wood-based domestic component used with peat or coir that’s available in many formulations.

Sugarcane bagasse (Figure 1F) officially made its debut in hybrid mixes in 2025 after years of R&D validating its potential. And some novelty materials currently used in some small-scale regional growing operations or still in the developmental R&D phase include processed bamboo fiber (Figure 1C), miscanthus (Figure 1I) and kenaf made from hibiscus plants (Figure 1H). Due to the limitations of each of these materials as stand-alone substrates for most crops, the key to creating successful hybrid mixes in most cases is the continued reliance on peat at incorporation rates of at least 40%.

“Marrying” peat with other components

“Marrying” peat with other components

“Love and marriage, love and marriage, they go to together like a horse and carriage”—the Frank Sinatra classic made popular by 1980s sitcom “Married With Children” is a theme that can be applied to peat and non-peat substrates. The use of alternative components has been viewed by many in the industry as direct competition to peat and other traditional materials (perlite, coir, etc.) and thought to be full replacements.

I think the more realistic and truthful viewpoint is to understand that no other material is peat or will ever be peat, so peat cannot be “replaced.” Other materials are not often direct competitors, but instead the combination of them together—the “marriage,” if you will, creates unique hybrid mixes (Figure 2). To borrow another common proverb, it takes a village to raise a child, and as we look to solve the challenges of addressing future substrate supply uncertainties, renewable non-peat materials are, and will remain, necessary components to better ensure stable supply chains in the future. Additionally, domestically sourced substrate components can offer potential economic benefits by reducing overseas transport costs, improve job creation and provide an overall boost to numerous small/rural communities across the country where materials are sourced and processed.

To take a closer look at the “marriage” of peat and other materials, an up-close external view of wood fiber and peat depicts the differences in their fibrous nature (Figure 3). These physical differences are a result of the processing of the materials, or the inherent anatomy and structure of the different plants (wood vs. peat). An internal view of the materials using x-ray tomography illustrates the viewpoint of plant roots in the substrate (rootzone) matrix. The beauty of engineered and crafted hybrid mixes is the functional improvement of porosity, water movement and root growth commonly seen.

Organic substrate components aren’t the only materials used in peat-hybrid mixes, though the conversation typically seems to revolve around them. Perlite remains a mainstay for many mixes, as it has for more than half a century, and while some growers have opted for other aggregate components to blend with peat, many still rely on this highly valued product.

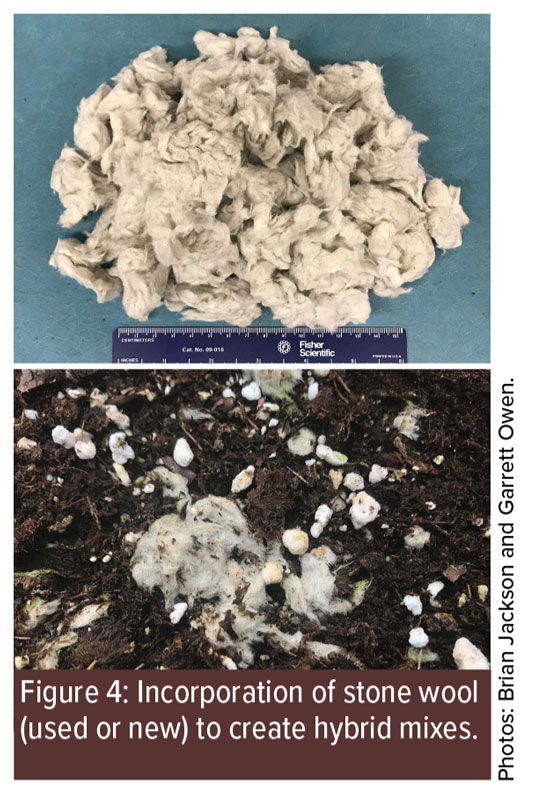

Mike Dunleavy, COO and President of P.V.P. Industries, recently noted that some perlite sales have shifted from going directly to growers and substrate companies to distributors and garden centers in response to consumers opting to adjust mixes or make their own to get the product/results they want. It’s also important to note that P.V.P., and likely other perlite suppliers, is currently processing ~50% of their perlite from domestic ore sources and that there are no indications of perlite shortages in the U.S. on the horizon. Another common inorganic material, stone wool, is used by some growers in their peat mixes as a means to repurpose spent wool materials and/or to create mixes with enhanced water properties (Figure 4).

There can be many reasons why growers may decide to trial new mixes, including: 1) new products may better align with sustainability goals; 2) the desire to support domestic product use; 3) more reliable product availability and supply year-to-year; 4) enhanced crop performance (sterile materials, improved mix biology, automation efficiency, etc.); or 5) cost of products and production inputs (water, fertilizer, crop shrinkage, retail shelf life). It’s advisable to try new growing media recipes to gain some experience and knowledge about how to switch growing practices, if and when needed.

To quote my Ag teacher in high school, Danny Kinlaw: “The time to dig ditches is during droughts, not when it’s raining and you’re knee-deep in water.” Taking a proactive, forward-thinking approach to new or hybrid substrate mixes can prove beneficial, as many growers over the past decade have openly stated. When trialing new mixes, the learning curve doesn’t have to be as steep or treacherous as some folks often fear it is.

Apples and oranges

When conducting on-site trials with new substrate components or hybrid mixes, it’s important to include your standard (normal) mix as part of the trial—at least the first time as a reference point. Starting with a 20% inclusion rate (added to peat) of new components is a fairly safe approach for initial trialing. Increased inclusion rates can follow (or done simultaneously if desired) to identify the incorporation threshold that results in significant changes in crop management.

A good first approach is to treat new mix(es) the same as your traditional mix with regard to irrigation and fertility management, and observe plant performance during the production cycle. After assessing the results—if plant growth, health, finishing time, etc. in the trial mix(es) is not on par with your traditional mix—don’t immediately assume it isn’t still a viable option since you’ve basically compared “apples to oranges.” Conduct the trial again, catering to the specific water, fertility, pH, etc. needs of the plants in the trial mixes, independently of how you typically manage your crops. Dialing in the optimal input needs and timing for new/different mixes (you’re now comparing “apples to apples,” so-to-speak), you can better assess the performance of the trial mixes in your operation. If working with a substrate supplier to conduct trials, lean on them for their technical guidance and input regarding results and next steps.

The trialing process could be analogous to parenting: You figure out how to raise your first child (growing in peat mixes) then try the same approach on your second child (new mixes) only to find out that the new kid doesn’t respond to the same strategies that led to success the first time. Parents learn to pivot, change the game plan and provide what’s needed, when it’s needed. Growers who do the same when trialing new mixes are more likely to succeed in determining the overall acceptability of new products.

To make the point in another way for the car enthusiasts among us, cars built today don’t drive like cars built in the 1950s; therefore, they cannot be driven the same way. Learn to “drive” new hybrid mixes according to their own abilities and speed limits.

When deciding whether or not to explore new substrate options or hybrid mixes, cost is usually one of the leading factors. However, cost of the substrate itself should be looked at more holistically to include any associated increased costs of other inputs needed to maximize or optimize plant growth during production. “Full cost of ownership,” a business philosophy shared with me by members of Pittmoss LLC, is an understanding (by the grower) of how existing production costs (water, fertilizer, labor, shrinkage, etc.) change when switching to new substrates. They recommend that this “substrate economy” cost assessment can be made by conducting in-house trials or by evaluating research study data on the new products. Bottom line: The up-front delivered substrate cost should not drive immediate purchasing decisions without considering all cost changes throughout production. (Remember: Different kids need different resources and may incur different expenses.)

In light of no definitive answers or product performance guarantees for all users, no single component solutions or no industry-wide standards for growing media needs in the future, the best approach is to strategically find what’s best for you, your crop production system and your bottom line. Without a doubt, the growing media industry is working tirelessly to address current and future substrate challenges through their investment in R&D of new products and their focus on inventing the future of next-generation substrate products.

To summarize something Mike Dunleavy told me (and I agree): “If everyone in the industry [growers and substrate suppliers] would work together to capitalize on the positive attributes of different media components, focus on the values that each may offer and work together to complement one another, when possible, we would all be much better off.” I think that mindset could help us all in this industry evolve, adapt and be best prepared for the production challenges, known and unknown, that lie ahead. GT

Dr. Brian E. Jackson is a Professor and Director of the Horticultural Substrates Laboratory at NC State University. Brian can be reached at Brian_Jackson@ncsu.edu.