11/28/2025

Two-Spot Cotton Leafhopper on Hibiscus

Muhammad Z. “Zee” Ahmed

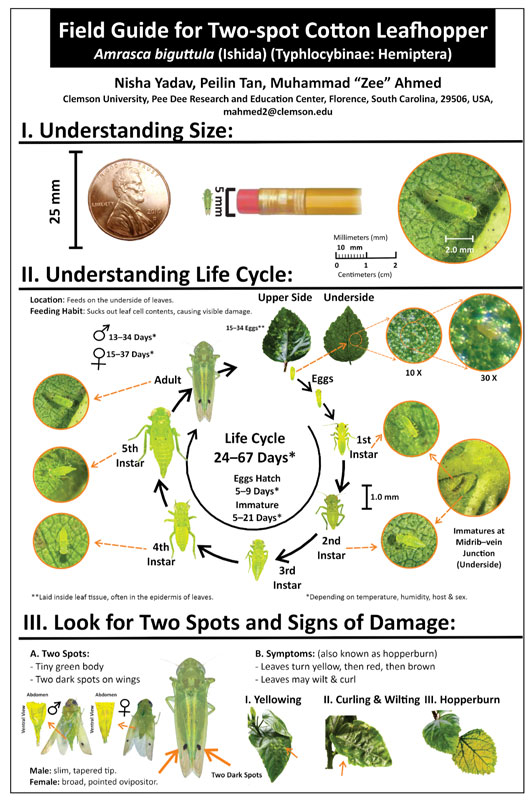

If you grow hibiscus, watch for the two-spot cotton leafhopper (TSCL; Amrasca biguttula). Originally from Asia, TSCL was first detected in the Caribbean in 2023, then in Florida in 2024, and in several southern states in 2025. Infestation by this small insect is often noticed only after the “hopperburn” symptom has appeared: green leaves turn yellow, then red, brown, curl and wilt. Females insert eggs singly into leaf veins and midribs, which makes early detection difficult. The seemingly uninfested plants are shipped, which spreads the insects.

Where TSCL is showing up and which plants to watch

TSCL is currently reported from Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Texas at the time of this publication, but it’s expected to expand further. States outside the current distribution are at risk when they receive hibiscus or other susceptible ornamentals from the affected states.

TSCL attacks many plant species, including agronomic crops, ornamentals and vegetables. Key hosts of TSCL include cotton, eggplant and okra. Other crops that can sustain TSCL populations include cowpea, mung bean, peanut, potato, soybean and sunflower. Members of the mallow family (Malvaceae)—including hibiscus, okra and roselle (grown in parts of the southeastern U.S., particularly Florida, where it’s called “Florida cranberry”)—are especially important because they’re refuges when the main agronomic crops are not in the field. Reports from other countries document severe injury and yield losses of 30% to 50% in susceptible crops.

My students, Nisha Yadav and Peilin Tan, and I are currently studying the biology and management of TSCL on hibiscus at Clemson University’s Pee Dee Research & Education Center in Florence, South Carolina. Here are the preliminary findings on its biology:

Eggs: Eggs hatch six to nine days after they’re laid in the summer, according to published studies.

Nymphs: There are five nymphal instars. We observed that each instar lasted two to three days, with egg-to-adult development taking about two to three weeks during September and October in field cages. Nymphs feed primarily on the underside and along the veins of leaves. Adult males live about 13 days and females about 15 days in our observations.

Host effects and seasonality: Based on our study, its development on hibiscus tended to be slower than that reported from okra and cotton. We also found that in an area with many host species, staggered waves of adults were produced because the timing of development differs by host species.

Cold survival: In our short cold exposure test, chilling 39 to 41F (4 to 5C) for seven days killed almost all first to third instars and adults, but eggs and fourth and fifth instars survived.

What we tested and why

We ran an insecticide screening trial on 5-gal. infested hibiscus plants. Plants were held on a screened outdoor nursery pad for two months to allow populations to stabilize. Adults and nymphs at the top, middle and bottom of each plant were counted at seven and 14 days after treatment to capture quick knockdown and short-term residual performance.

The treatments tested were chosen to represent major IRAC groups or modes of action, as well as contact, translaminar and systemic materials. Treatments were Hachi Hachi SC (tolfenpyrad, IRAC Group 21A) at 26.5 fl. oz. per 100 gal., Altus (flupyradifurone, Group 4D) at 8.75 fl. oz. per 100 gal., Mainspring GNL (cyantraniliprole, Group 28) at 5 fl. oz. per 100 gal., Ventigra (afidopyropen, Group 9D) at 5.9 fl. oz. per 100 gal., Safari 20SG (dinotefuran, Group 4A) at 6 fl. oz. per 100 gal., and Talstar Professional (bifenthrin, Group 3A) at 16.25 fl. oz. per 100 gal., and an untreated control. Mainspring and Ventigra are not registered for use against leafhoppers, however, they were included in this study because of their documented translaminar or systemic activity against other piercing–sucking insect pests.

Key results and what they mean

Tolfenpyrad and flupyradifurone produced the most consistent reductions in adults and nymphs at both seven and 14 days. Cyantraniliprole gave fast adult knockdown at seven days, but counts rose again by Day 14. Dinotefuran and afidopyropen reduced counts compared with untreated plants, but the effects were variable across replicates. Bifenthrin showed mixed nymph suppression.

In summary, products with translaminar or systemic activity tended to perform better against nymphs feeding on the leaf surface. In general, insecticides cannot kill TSCL eggs because they’re well protected in plant tissues; consequently, new nymphs will continue to emerge after treatment. Because of this, repeated applications are required and the appropriate interval depends on the residual activity of the product. Some insecticides may provide suppression for up to 14 days after treatment, while others may require weekly reapplication.

Practical takeaways: Match the product to the life stage (instars and adults) you find, check treated plants at seven days for newly hatched nymphs and again at 14 days to confirm suppression.

Studies from the species’ native range report reduced sensitivity to some insecticides. Treat this as a practical warning: You should rotate products by IRAC group, avoid repeated use of the same chemistry, and use non-chemical tactics such as conserving natural enemies and improving cultural practices to reduce spray frequency and delay resistance.

Recommendations you can use at this stage

- Scout with a 10 to 30× hand lens regularly. Inspect the undersides and veins of leaves on the top, middle and bottom of some plants. Record date, location and what you find.

- Treat when TSCL is found. Do not assume products for other pests will control TSCL.

- Match treatment to the life stage: Systemic or translaminar choices for nymphs; quick knockdown for adults. And follow up with scouting at seven days to catch newly hatched nymphs and again at 14 days to confirm suppression and determine if reapplication is needed.

- Rotate among IRAC groups and keep a simple spray log that lists dates and IRAC groups used. Use biological and cultural tactics where possible.

Bottom line

TSCL is small, but can cause big aesthetics and yield losses when it becomes established. Because eggs hide in veins and nymphs feed on the leaf surface, routine scouting, life-stage-based product choice, timely seven- and 14-day checks, and IRAC rotations are the most practical steps to keep small problems small and protect production and marketability. GT

Muhammad Z. “Zee” Ahmed is an Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist of turf and ornamental entomology at Clemson University.