7/1/2024

Staying on Financial Course

Jennifer Zurko

When I asked Barry Sturdivant, a long-time green industry financial expert and consultant, about what causes a greenhouse operation to close up shop, he told this story: “I just got back from a trip across northern Spain. It included a stop in Pamplona. Some traveling companions and I went into a restaurant where we unexpectedly came across a bronze statue of Ernest Hemingway sitting at the bar holding a drink. I actually raised a toast to him for giving me a quote I use in presentations to nursery and greenhouse groups to make my point about the need for proper working capital and maintaining proper earnings. The quote is from Mike, the main character in ‘The Sun Also Rises.’ Mike was asked how a company goes bankrupt to which he replied: ‘... in two ways—gradually, then suddenly.’

“Any greenhouse or nursery business I know of that’s been dropped by a bank or has had to go out of business had the signs of financial stress 10 years earlier.”

Bankruptcy doesn’t happen overnight; it’s a death by a thousand cuts, happening slowly over time. There are always warning signs, which some choose to ignore; some cross their fingers and hope one good year will make up for a few so-so ones. Regardless, there are ways to avoid getting too close to the cliff or completely going over.

A difficult financial landscape

If you’ve noticed that it’s been harder for agricultural businesses to get access to capital in recent years that’s because it is. Barry said, traditionally, banks have always considered agricultural businesses high risk, but there were ways to leverage losses with tangible assets, like for dairy farms you can always sell the cows. For businesses with seasonal and perishable products (like greenhouses)—where one bad year can wipe you out—it’s harder to convince lenders to take those risks.

Today’s economic environment has made it much harder for growers to get access to capital for a number of reasons. I sat down with Ball Horticultural Company's CFO Jacco Kuipers to get his take on why it’s difficult for growers to secure financing.

1. Current interest rates—It costs more to borrow the same amount today than 10 years ago.

2. Less leverage—In order to loan out money, the bank has to have that cash, and more, on hand. “Banks need enough of their own capital to withstand any stress,” said Jacco. Not having a “capital buffer” is what gets banks into trouble.

3. Inflation and the aftershocks of the Great Recession—It was over 15 years ago, but the banking system is still feeling the rippling effects from the economic downtown in 2008. “Since the Great Recession, the Fed pumped a bunch of money into the economy with treasuries through the banks,” Jacco explained, saying that it equaled about $60 billion a month for more than a decade. “It only caused a slight economic uptick. When something goes awry—like COVID—it causes inflation.”

4. COVID-relief programs—It may have put some temporary money in the pocket of Joe and Jane Public, but it caused high demand for products, which stretched supply to its breaking point. Couple that with low unemployment and inflation “and you have the perfect storm,” Jacco said.

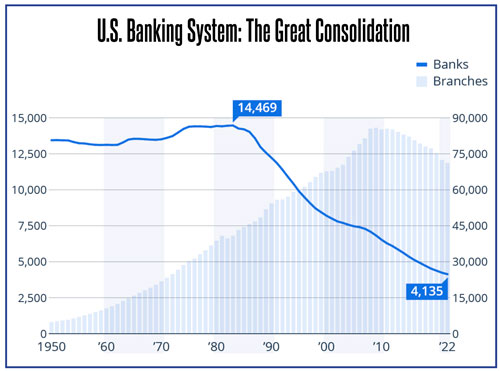

There are also fewer banks out there to borrow money from. As smaller banks failed during the Great Recession, the larger conglomerates gobbled them up, contributing to a decades-long consolidation trend in the banking sector.

According to the FDIC, the number of U.S. banks decreased drastically from its peak in the early 1980s (see the chart). Forty years ago, there were 14,469 commercial banks in the United States. By the end of 2022, that number was down to 4,135. Those remaining banks operated 71,190 branches at the end of 2022, up from just over 40,000 in 1983.

If your bank drops you, where can you get money?

If you don’t have access to capital, where can you get it? Barry said there are some options.

An underused and lesser-known source of capital are loan originators who can access Farmer Mac funding. Farmer Mac was formed after the Farm Act of 1986 as a secondary market for farm loans. Think of it like Fannie Mae, but for agricultural land loans.

These lenders can loan up to $50 million and their focus is family farms. And they can loan up to $3 million based only on a credit score. They also offer real estate-secured lines of credit with a draw period of up to 10 years.

These lenders can loan up to $50 million and their focus is family farms. And they can loan up to $3 million based only on a credit score. They also offer real estate-secured lines of credit with a draw period of up to 10 years.

“These originators are a little harder to find, but many of them are experienced agricultural lenders who believe in relationships,” said Barry. “Banks and Farm Credit are, of course, still around and easier to find. Many still do a great job, but their recent inclination toward a transactional approach, instead of fostering relationships, is a concern. This is where being in ag and especially horticulture can be an advantage.”

Pictured: Number of FDIC-insured commercial banks and branches in the United States from 1950 to 2022. Source: FDIC and Statista.

Another option? Ask a peer or even a competitor if they like their lender and if that lender is capable of offering occasional advice and guidance. Banks may now be big conglomerates, but word-of-mouth reviews still hold a lot of weight.

There’s also the option of turning to private equity firms to get working capital, but as some greenhouse businesses have learned, that can come with more risks than rewards (see sidebar). Regardless of where you find money (even if it’s a loan from a rich uncle), you need to be aware of every risk and benefit. And you need a contingency plan if it doesn’t work out.

Keeping your banker happy

It’s true that the days of having your choice of locally owned village banks to turn to are gone, but having a good relationship with your lender is the same. Because you’re probably dealing with a large national institution, you’ll have to work harder to maintain that relationship and it may not be as chummy as if it were someone who grew up in your town. But you need your lender to know who you are.

“Make sure that if you get into trouble, it’s not the first time they’ve heard of you,” said Jacco.

As one of the co-owners and co-CEOs of Metrolina Greenhouses, Art VanWingerden is all too familiar with working with lenders and analyzing financials. Art has a little red book that’s been used to keep track of Metrolina’s finances over the last 20 years. At the end of every month, he knows where the cash has been and where it’s going. And Art and his brother and co-CEO Abe VanWingerden meet with Metrolina CFO Jim Shiller once a week to make sure everyone is on the same page.

Metrolina meets with its lenders constantly, and because they have such a strong handle on their finances, those interactions continue to be beneficial, even if there’s personnel turnover at the bank. That history of positive exchanges is there, regardless of who’s behind the desk.

“Some business owners don’t interact with their banks but once every six months or once every 12 months. And then they're shocked when the bank goes, ‘Hey, man, you're just not doing well,’” said Art. “We are in contact with our bank all time. I want our banker coming here. Come look at what we're doing. See how we’re doing it. Tell me what you see. Tell me what’s wrong. So we stay in contact. We have communication with our banks today so that we know where we stand with them. And I think a lot of people are missing out on that.”

And if there’s a point when you’d like to invest more into your business, they’ll be more willing to work with you if they know you.

“Communicate with your banker,” said Barry. “Talk to that person and, and let them know, ‘Hey, I had a great year and I’ve got an opportunity to build my business in the next year.’ Or you got in with a new customer and you say, ‘I can make those sales, but I need the capacity to do it.’ They’ll most likely give support and some cash to put into that new greenhouse.

“Don’t take [your bank] by surprise. And don't let them become transactional; work on the relationship. Go and visit them, get to know them, let them know you, let them see you. It’s not easy, but I would go to the effort.”

Life rafts in the form of advice

If you’re finding yourself in a recent cash crunch and worried that you’ll be dropped by your bank, Barry said it’s never too late to correct course. Here are some tips to avoid financial pitfalls:

Be nimble so you can avoid the iceberg. Don’t do the same thing year after year. Know your winners and losers. Really analyze the data on what’s making you money and what’s sucking you dry. On the surface, it may look like you’re selling a lot of a particular product, but it could be costing you more to produce it on the front end.

And don’t ignore your finances. You should be looking at the books at least once a week. This way, if you see any possible future pitfalls, you can try and plan ahead to avoid them.

As one of the largest operations in the U.S., Art compared Metrolina to a large ship, which you can’t just turn on a dime, so he and his team have to be constantly aware of the direction they’re going in to avoid any major issues.

“We can hit a few little ice chips, but I don't want to hit an iceberg,” said Art. “And if I only look at [my financials] once a year, there’s going to be an iceberg coming at me. If I see it coming, I can move around it and I’m okay. So how do we make sure you move around that iceberg if you just keep your head down and going no matter what? You don’t. The iceberg always wins.”

Don’t be reactionary. Pay attention to the trends, try some things, but don’t push all your chips in.

Be smart with your cash overflow and where you need to tighten your belt. Even in bad years, most operations make a little bit of money. Put some aside to help pay down any long-term debt. And in the good years when you’ve got more in the coffers after spring, don’t run out and buy a new greenhouse or transplanter right away. Crunch the numbers and see what the return will be on those major investments.

And if you find yourself behind because of a bad year, don’t start slashing things at the top. Many short-term cutbacks can end up negatively affecting you longer term.

“It’s just keeping up with your debt. When you have a bad year and lose money, do you try to shrink back a little bit? If you don’t, you just get into more trouble. Then you don’t have the income to even service the debt you have,” Art said. “I'm not saying you’ve got to grow by 10% when you have a bad year, but if you get tight on the wrong things—don’t give people raises, can’t do benefits—you start losing good people. Then the downhill slope is, unfortunately, very, very quick.”

Work with your suppliers. You’ve maintained that long-term relationship with the suppliers of your plants, growing media, fertilizer, etc.—if you’ve got some extra cash after a decent year, ask them if you can get a discount if you pay early for next year’s inventory. The money you save up front may end up being a saving grace if the next season isn’t as good.

Make sure you don’t have a lot of long-term debt. That loan you took out for the new greenhouse may have been fine when you took it out two years ago, but are you still able to afford to pay it when the interest rate is above 8% like it is now? Plan for multiple scenarios so that it doesn’t take you longer to pay off a loan. Or worse—not able to pay it at all.

When you do earn a line of credit, use that money wisely. It should be used to get you through until you accumulate all of your sales for the season, said Barry. Once you do, use that profit to pay off the loan and, ideally, sock the rest away. Unfortunately, the temptation is to use any profit for major investments (like a transplanter or a new greenhouse) before paying off the loan, which automatically puts you behind the eight ball.

“If you’re going to maintain the same business next spring as you had this year, and you got no reason to think you’re going to increase your sales or at least your units, hang on to the cash,” said Barry. “No one likes to hang on the cash and see it sitting around doing nothing for them. But, boy, it's nice to have when March comes around and you’re sweating out payroll.”

Honestly assess your financials on an annual basis. Barry recommends asking yourself the following questions to stay out of trouble and in the good graces of your lender:

1. Did you meet all of your payroll on time?

2. Did you pay your suppliers on a timely basis?

3. Were you able to take advantage of any offered trade discounts?

4. Did your inventory increase result in sales growth?

5. Did your sales growth result in increased profits?

6. Are your principal loan payments on the term debt, plus non-financed fixed asset expenditures less than your net income plus depreciation?

“If the answer to any of these questions is no for two of the past four years, consider a term loan against your real estate to use the cash to reduce your current line of credit or to pay down your accounts payable,” Barry advised. “It is the inability to access the short-term debt that will get you in trouble. To make sure you have the short-term debt to get through a bad year, you need to be ahead of the curve and leverage your long-term borrowing ability as you navigate through the better years. Don't hesitate.” GT

Using Private Equity: Don’t Be Shark Bait

Jerry Halamuda has been in the horticulture industry for over 50 years. He was the previous owner of Color Spot that started with a love of plants with his friend Mike Vukelich (who passed away in 2010). After years of unprecedented growth, they wanted to continue to grow their business, so they turned to a private equity firm for access to more capital. It worked for a while, but when the private equity firm forced them to acquire Hines Nursery—an operation that was struggling financially—the large amount of debt that came with it was too much weight to carry. That, along with a loan structure that didn’t fit with a nursery business and a finance person who went to extreme cost-cutting measures, sunk both operations and the bank forced them to liquidate.

Today, Jerry is still involved in the green industry—mostly in e-commerce—and educates other business owners on what he’s learned from the experience.

“It’s the capital required and then the requirements of the capital source that’s the killer. And that’s where a lot of people get in,” he explained. “And I would say the majority of the growers that I’ve talked to over the years, when they went out and started acquiring outside capital wherever the provider was—investment banking, private equity, you name it—wherever that capital was, they really did not understand what the impact was going to be.”

Wells Fargo and BMO Harris may be fine if you’re getting a personal or car loan, but most of the large national banks don’t have specific financing for ag/hort businesses. And if they do, the lending terms offer no wiggle room.

“If the performance isn’t there and you’re a banker, you’re at zero right out of the box, because institutional lenders don’t have the system in place to manage businesses that are having cash flow problems,” said Jerry.

And with fewer banks willing to offer loans, growers who want to invest more into their business with expansion or acquisition are turning to other means of acquiring capital, which comes with risks they may not even be aware of.

“What occurs is that if you don’t find the capital, you’re going to go over to the sharks,” said Jerry. “And when I say sharks, that can be private equity, venture capital, angel [private] investors. It could be any number of different types of sources of capital, but they’re all going to cost you significantly more. The first eight months they’re going to work with you, but they’re going to increase the fees if you want an increase in credit. It’s just the way it is. They’re giving you money, but they expect some in return.

“A lot of times people come into a situation where things have been a little rough. They’re a little distressed and they’ve got to find a way out. Now who do they go to? The only answer is to go to private equity because they’re the only ones who accept the risk. There are some winning stories and, of course, private equity can help you improve your business, but unfortunately, what happens sometimes is, when you get into bed with the sharks, you gotta pay the price.”

—JZ