7/1/2021

Inputs: Over & Out

Jennifer Zurko

In the 1930s, Toyota created what’s referred to as “Just In Time Manufacturing.” In a nutshell, the whole point was to deliver automobile parts to assembly factories when they needed them, instead of having their customers order in bulk and stockpile the parts in a warehouse somewhere.

One theory is that Toyota wanted to “solve the lack of standardization.” But the more realistic reasons are because the country of Japan lacked the space and natural resources to make a bunch of parts at once and hold on to them until someone placed an order. After WWII, having to rebuild with a significant lack of labor also forced Toyota to streamline their processes. They were the first ones to really practice lean manufacturing.

Over the last half-century, many other industries adopted this measure. Just In Time offered businesses a way to adapt to changing markets and consumer demands—all while cutting costs.

But, like many other things, we’ve realized that Just In Time isn’t pandemic-proof. Some businesses have run so lean that when they needed something from their own suppliers—who’ve also been running lean—there were no raw materials to be had. It’s been like a vicious snowball rolling down the supply chain. The result is shortages on a wide range of goods. You thought the toilet paper shortage at the beginning of the pandemic was ridiculous? Try buying lumber or a car right now.

Just In Time isn’t a failed experiment, by any means. It revolutionized the business world, opening the door for innovation and opportunities to better service customers, and promoting global trade. But what the COVID-19 pandemic brought to light is that this approach can have a significant, far-reaching impact when you don’t plan ahead and there’s a major disaster.

The New York Times had a piece on the recent shortages (“How the World Ran Out of Everything”) where Knut Alicke of McKinsey said companies have been acting like manufacturing and shipping were trouble-proof. He was quoted as saying, “We went way too far. There’s no kind of disruption risk term [in current business plans].”

In our industry bubble, we’re hearing about shortages and delays on everything from plug trays and pots to chemicals and poly film. Many growers and retailers reported another great sales year—some saying it was even better than last year’s spring season. But we’re also hearing how some of them were doing it while having to reuse trays and rationing growing media.

I asked a handful of hardgoods suppliers if they’ve had any challenges with regard to shortages and delays, how they were able to deal with it while still servicing their customers, and when they think the warehouses will be full once again.

Greenhouse Materials

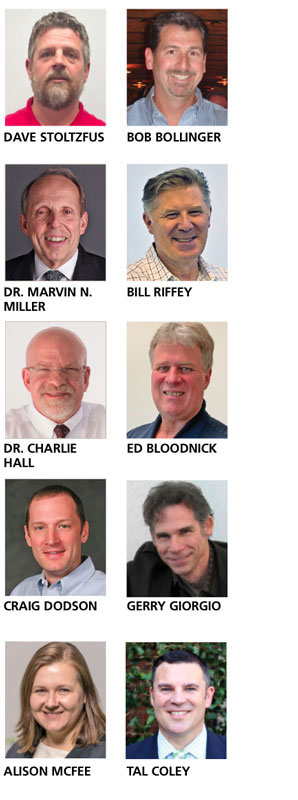

Dave Stoltzfus

President—Advancing Alternatives

Lead times are a huge challenge. Aluminum extruders are out 10 to 12 weeks, up from three to four weeks a year ago. We’ve also been put on monthly allocations for extruded aluminum and that may last until the end of the year. Steel tube and pipe mills have extended lead times because of raw material shortages. We’re also seeing raw material shortages for stainless wire, which is what we use for our zig-zag wire (wiggle wire). The stainless wire has been coming in three to six weeks late, which has resulted in our production being shut down for weeks at a time. (Dave says steel, aluminum, stainless, electronic parts and environmental controller components are the materials they’re struggling with the most.)

We hope to be back to normal by fall of 2021 or spring of 2022 at the latest. This will depend on how profitable growers were in the spring of 2021, and whether they’ll expand or improve their operations in the summer of 2021.

Advice for their customers: Don’t undersell your products—create value-added products for your customers, plan ahead by three to four months and expect 30% to 40% increased costs when expanding or building new structures.

We’re advising smaller growers to automate as much as possible. This will reduce their payroll and increase their bottom line. It’s never been easier to automate small high tunnels and greenhouses, and the ROI is often between one to two years. Automating side walls and roof vents also creates better growing environments that result in a better plant at the end of the day.

And expect higher prices—we get on average two or four notices a month from our material suppliers. Unfortun-ately, that will be passed on to the growers.

Chemistries

Craig Dodson

Head of Supply Chain—Bayer Environmental Science in the U.S.

We currently are in pretty good shape in our Ornamentals segment due to the nature of our production cycles for that portfolio. In a broader sense, there have certainly been COVID-related supply chain interruptions in our industry, as well as a multitude of others. The biggest impacts we’ve seen have been on the transportation and packaging sides.

As a global company, we source materials from around the world. We generally keep inventory of key items on-hand to manage the occasional supply interruptions, so we didn’t really start to feel an impact until late summer or early fall last year.

On the import/export front, not as many ships were moving freight and the COVID-related items took priority, as they should have. There were also fewer trucking companies operating and those that were had reduced staff. So, eventually, that’s going to catch up to nearly every industry to some degree.

On the packaging front, we were seeing lower supplies of things like bottle caps where inventory was being redirected for hand sanitizer and paper for label production, wherein, again, items needed for the fight against COVID were taking priority.

It’s honestly tough to know definitively on the transportation side [when things will catch up]. Our friends in India are seeing a COVID resurgence, which will redirect/reprioritize some materials to them to help in that fight, and it could have some ripple effect. Though, on the truck-fleet front, we’re working with alternative companies to help fulfill our needs in the short term.

On the packaging side, we’re getting our hands wrapped around that and expect to be back to “normal” in that regard by the summer/fall time frame.

Advice for their customers: As noted, we’re in a good place with our Ornamentals portfolios right now and have worked to limit other impacts. That said, we’re employing alternate sources to have multiple options and we’re increasing our purchasing lead times to stay ahead of potential issues. We always recommend that customers keep their forecasts updated and that they stay in close communication with their Bayer and/or distributor sales rep so that the reps can, in turn, effectively manage expectations with manufacturing on what’s needed and when. Communication is always important, but it’s even more so when there are a lot of variables at play like this. It’s always our goal to put our customers’ needs first and we’re making adjustments accordingly as circumstances evolve.

Alison McFee

Head of Marketing—Bayer Turf & Ornamentals in the U.S. on how pricing is affected by the shortages:

We’re trying to minimize impact to customers by actively tracking the rising costs and mitigating them when possible. At this point, our product pricing is holding in the marketplace. Should we see sustained increases in our input prices, we’ll likely have to integrate this into our product pricing. We’ll proactively communicate any change through our sales reps and channel partners if/as the situation changes.

Growing Media

Bob Bollinger

CEO—ASB Greenworld

For the past 15 months, demand for growing media and most products in our industry has greatly increased. We’ve been able to keep up with this increase until recently when the shortage of perlite in the industry has gotten critical. Perlite suppliers are allocating perlite to all growing media manufacturers, therefore our availability of grower media with perlite is limited by the shortage of perlite.

We’ve been given several dates when supply might be back to normal, but the dates have come and gone. The situation hasn’t improved and other suppliers everywhere are also experiencing shortages on things such as pallets, plastic, wetting agents, trucks and labor. When the raw materials are available, ASB Greenworld will have no issue catching up since we have the machine capacity to do more. I think it’ll be the summer of 2022 before supply is back to normal since it’ll require capital investments by suppliers and this takes time.

All of these shortages are resulting in all raw materials costing more, so we must raise prices. We normally raise prices once a year. In the past 12 months, we’ve raised prices three times, which causes a lot of confusion and stress in the market for everyone. The current peat moss harvest is in progress, and as many of our competitors are doing, we’re not planning to sell straight peat moss. ASB Greenworld is committing all our peat moss resources to making our own grower mixes since there’s a worldwide shortage of peat moss, too. Growers should order early since more price increases are expected between now and the end of the calendar year.

Advice for their customers: The best thing that customers can do to manage this is to order early and look at alternatives. Many growing media suppliers are offering perlite-free mixes. ASB Greenworld offers grower mixes with HydraFiber from Profile Products. By using a 1-to-1 replacement of perlite, our HydraFiber mixes have growers telling us about better root development, no change in grower practices other than watering less and growers can catch up to the demand of their orders with faster growing times to bring plants to market. The best advantage is that we can supply a grower mix made with HydraFiber sooner than a perlite mix since the raw materials are readily available.

Bill Riffey

Global Director—OASIS Grower Solutions

Supply of raw materials and increased demand has created a cascade affect that’s pushing our manufacturing to work overtime to keep up, and when supplies don’t come in a timely manner, we’ve been able to offer substitutions and/or ration supply to align when cuttings are arriving. Cuttings need a home when they arrive and our role is to make sure they have a substrate to put the cutting in.

I’m not sure what “the new normal” is when supply will stabilize. We’ve been making changes as an organization to stabilize our supply chain by ordering earlier and building inventory to respond to last-minute customer demands.

As with everyone, we’re seeing price increases in raw materials, especially in plastics. The driving shortage in labor is also driving our costs. People are getting harder to find and wages are rising rapidly. And freight is the other factor where we’re seeing increases.

Advice for their customers: Customers can order earlier by bringing product in earlier than they have in the past. The other point is to be open to substitutions. Normally, there’s another configuration of trays available.

Ed Bloodnick

Director of Grower Services—Premier Tech Growers and Consumers

For our company, we have adequate resources of sphagnum peat moss and processed aged bark for manufacturing growing media. However, some of the ingredients that we use are from overseas—for example, the mineral ores for perlite and vermiculite are brought in by ships. COVID-19 also had impact for domestic ingredients due to worker limitation and supply chain disruptions.

I think many of the growing media companies were faced with the same situation that there just weren’t enough raw materials to go around due to disruptions in the supply chain. If garden centers are selling 30% more flowers and plants, and growers are growing 30% more, then 30% more growing media was required. Overall, all of the crop supplies that growers needed were delayed because of shipping and supply chain disruptions.

Some of our products contain coir, so at one point, there was a lockdown with COVID in India and Sri Lanka last year. Things started to get a little bit better going into late fall before Christmas, but we had another hit again in India because of the COVID variant.

When you order these ingredients from overseas, it can take four to six weeks before it is delivered, so we had to limit some of our products because we weren’t able to have all of the ingredients that we wanted. For our mainstream products, we were able to supply these, but that also meant that we had to step up our production and increase volume above normal capacity by working two shifts, and in some cases, three shifts. This put some strain on labor, since more team members were required, and with COVID, we wanted to be sure workers are safe.

One benefit for PTGC is that we have multiple facilities across Canada and one in Virginia, so we were able to move product across North America. We had to do a lot of cross-shipping to make sure that we could supply our customers. We definitely experienced some delays, but we did our best to service customers and ensure that they received their deliveries. And I think overall, our customers understood the delays, since they were facing a disrupted supply chain from all angles for all the materials they were buying.

We are catching up. I know at some point we were looking at three weeks, then four weeks or more. Our normal turnaround time in previous years was two to three weeks on most orders.

Our distribution network has played a vital role. If we’re not able to deliver a truckload, customers still can get a couple pallets from a distributor, so we always want to make sure the distributors have inventory. And in some regions, customers had to go to a distributor to get a pallet or two until the truck came. And that’s okay— they didn’t run out and they were able to get through the planting season until their delivery arrived.

We’re getting closer to normal now. Spring is always the crunch time because it’s the season when the most amount of growing media is shipped out. As an industry, we all take a little breather after Memorial Day and then it slows down a little as we enter into July, so that gives all of us a chance to catch up.

Plastics

Gerry Giorgio

Creative Director—MasterTag

With regard to our source of supply for our products, we’ve thus far been able to supply what we’ve needed for our production. But where we’re really feeling it is the impact on cost due to tight supplies of the raw materials needed to produce the plastics.

An already tight resin market, as well as unexpected weather events in the Gulf Region (which is the primary hub for all plastic resin production and U.S. supply), has resulted in a situation that’s causing resin supply volatility across all polymers/resin types, including major supply disruptions, greatly extended resin lead times and continued resin price increases.

So far, our customers have been accepting of price increases. I think they’re seeing them from all vendors and have been expecting them to a degree.

Regarding a return to “normal,” I’m really not sure. The plastic industry was having supply and price pressure on our raw materials even before the pandemic and weather events. So we anticipate some mitigation on costs as supply chains and production levels return. But I doubt that things will go back entirely to what they were before. We’ll continue to watch things and adjust to the market as needed.

Trucking/Logistics

Tal Coley

Director of Government Affairs—AmericanHort

There was a period there, probably March/April, where we were hearing—not only about freight rates that were exponentially more than they’ve ever paid before—but people couldn’t find trucks to get their materials to where they needed to go. On the macro level, this has kind of been boiling for a long time, and the pandemic added to the perfect storm.

The trucking industry has had some serious headwinds initially through retirements, increased regulation and then through the new generation not really wanting to take on that lifestyle. The American Trucking Associations has estimated that we need at least one million drivers over the next 10 years to meet the demand.

In one of my connector meeting calls, I heard there were some growers down in Florida who couldn’t find trucks that were refrigerated, so they just winged it and put the plants in a regular truck. So people are taking some chances around this. It’s kind of like the “Hunger Games” out there trying to find drivers.

Some people are taking measures that they can internally—some have H-2A workers that have CDLs and they’ll sometimes get them to drive. I did hear of a report from a firm sending some folks in their business to go get CDLs, so they had more people on staff that were available to drive a truck.

Anything AmericanHort focuses on in Washington, D.C., as a potential solution is going to be long-term. We did get behind the DRIVE-Safe Act, which has a lot of associations and coalitions behind it. The bill basically peels back some of the regulatory restrictions on younger commercial drivers 18 to 20 years old, which right now they cannot drive state-to-state. The logic behind it is, how can you have a guy with a CDL in California who can drive 600 miles and then you got a guy in Connecticut who can drive 50? So it sets up an apprenticeship program for young drivers where they complete a set number of hours with an experienced driver. What they’re trying to do is sweeten the pot a little bit for people who might want to make it a career. (The bill was re-introduced in the Senate in March, along with a companion bill in the House.)

The hope is that things will kind of moderate across the economy and we’ll be able to find more drivers as things die down, but right now, supply chains are stretched so thin among everything. We’re all fighting from the same pool to get our products shipped.

We’ve Never Experienced This Before … So What is a Grower to Do?

Dr. Marvin N. Miller

Research Manager—Ball Horticultural Company

Dr. Charlie Hall

Ellison Chair in International Floriculture—Texas A&M University

The extreme demand the horticulture industry has experienced during the last two years has been a delight for most (but not all) growers and marketers of floricultural crops. Reports of double-digit sales increases are common, with some reporting 20% to 30% increases two years in a row. Some retailers have facetiously reported selling everything except the gravel on the floor of their greenhouses, while others report selling the gravel as well. The hyper demand has been fun to experience.

On the other side of the equation has been supply. There have been more than a few postings of “cannot supply” this spring, as vendors have been unable to supply all that was being demanded. And, as you might expect, there have been multiple price increases as a result. This always happens when supply cannot meet the demand: prices do go up! What’s more unusual is that, for many products, there have been multiple price increases for some items, even within the same season. Industry reports suggest this may become more the norm, at least in the short term.

Throughout the current economy, as the concerns over COVID begin to ease and people get back to some sense of normalcy, we’re seeing what some economists are calling “transitory inflation.” This moniker is being used to describe the sudden increase in prices occurring as the result of the sudden surge in demand. When using this term, the anticipation is that prices will ease once the supply chain catches up with the demand. However, there are no guarantees, and when an industry has been starved for price increases over an extended period of time, there may be a reluctance to lower prices, even if the costs related to supply shortages ease. Certainly, the portion of the price increases being put in place to cover increased wages of everyone working throughout the supply chain may be more permanent, as could be some other portions of the increases as well.

In a very circular way, there’s corresponding concern about what effect heightened prices might have on demand. The National Gardening Association’s annual National Gardening Survey for 2021 has reported that there were 18.3 million new gardening households in 2020. Based on an overall U.S. population of about 128.5 million households, 95.8 million or almost three-quarters of which were engaged in one or more of the lawn and garden activities, these new gardening households almost guaranteed significant increases in industry sales. But the question on many minds is can all of these price increases be sustained without impacting the consumer’s willingness to buy?

From at least one perspective, there are some optimistic signs. Many of the new gardeners were young people, a demographic that’s been challenging older generations for dominance in the rankings for a few years now. Prior to the pandemic, these younger gardeners had already leap-frogged all but the Baby Boomers in terms of both lawn and garden participation and total spending on our industry’s products. The other good news is we’ve seen a surge in participation from groups that had previously been under-represented demographically, especially Blacks and Asian-Americans.

It’s interesting to note that we’ve seen this type of “shot-in-the-arm” increase in the industry during each economic downturn in the past 50 years. The “staycation” effect works in our favor and life is good. However, when the economy starts recovering and consumers start making the shift to purchasing durable goods (e.g., cars, furniture, appliances, etc.) and/or taking vacations again, that’s when our industry takes it on the chin. The jury is still out whether that will be the case this time because folks have already started making this switch and we’re still selling plants at a robust pace.

Disruptions in the supply chain, however, continue to limit our growth during this period of boosted demand. The main culprits are weather, residual instability from previous trade “negotiations” and tariffs, and continued COVID influences worldwide. Growers could grow even more product if their input supplies weren’t being squeezed (and/or being delayed during shipment).

Not only are some inputs in short supply, but their prices have also gone up significantly. In the latest Index of Prices Paid by Growers (which Charlie just updated), the forecasted weighted increase of all inputs that growers use to produce their crops (weighted by their relative importance in costs of goods sold) was 7.59% in 2021, and another 2.73% increase in costs is projected for 2022.

Since the projections in the table are based on the data available to date, please note that there will likely be further adjustments that manufacturers, distributors and other allied trade firms will make to their respective 2021 price schedules. Three in particular include: 1) plastics-related inputs where container and plastic sheeting prices are still in a state of flux, which are correlated to petroleum, resin and energy prices; 2) the trucking industry, where tonnage increases from e-commerce pressures are putting added demand pressure on already limited trailer supplies and driver shortages, and continue to influence short-term freight pricing; and 3) labor rates, since the methodology underlying the adverse effect wage rate is still in flux politically, as well as the ongoing discussions regarding state and federal minimum wage increases. Any of these factors (or other unforeseen events) would translate into higher/lower levels of input costs.

Since the projections in the table are based on the data available to date, please note that there will likely be further adjustments that manufacturers, distributors and other allied trade firms will make to their respective 2021 price schedules. Three in particular include: 1) plastics-related inputs where container and plastic sheeting prices are still in a state of flux, which are correlated to petroleum, resin and energy prices; 2) the trucking industry, where tonnage increases from e-commerce pressures are putting added demand pressure on already limited trailer supplies and driver shortages, and continue to influence short-term freight pricing; and 3) labor rates, since the methodology underlying the adverse effect wage rate is still in flux politically, as well as the ongoing discussions regarding state and federal minimum wage increases. Any of these factors (or other unforeseen events) would translate into higher/lower levels of input costs.

Looking across the entire green industry, given the actual (and perceived) plant shortages experienced this spring, there have been fewer complaints from both nursery and greenhouse growers of retail customers not honoring pre-booked sales. Growers have anecdotally commented on the increased difficulty of finding fill-in or substitute product. However, one thing we’ve learned in our collective years of working alongside this industry is that shortages can turn into surpluses in an amazingly short period of time. Given the very strong young plant sales this past year leads us to conclude that those young plants will magically turn into finished plants and, in time, we won’t even be using the word shortage much.

Bottom line, from the demand standpoint, never has there been a better time in three decades for growers to be raising prices. From the supply side of the coin, if you don’t raise your prices, then rising input costs are going to eat away at your margins. It’s your choice, but from the viewpoint of two industry economists, the time to raise prices is here.

One cautionary note: depending upon your customer segmentation strategy, you may want to have some products in your mix that offer introductory price points to attract these new gardeners or those with more limited dollars-per-plant budgets, who just might want to buy in quantity for planting in the ground. GT