6/23/2011

Medical Marijuana: Your Next Cash Crop?

Jennifer Zurko

Photography by Mark Widhalm

It’s ranked the No. 4 agricultural product in the U.S.* George Washington and Thomas Jefferson grew it on their farms. The Chinese used it 5,000 years ago to treat malaria and rheumatism.

So when editor Chris Beytes brought up the idea of doing a feature story about medical marijuana as a potential new niche for greenhouse growers, I immediately jumped into the conversation. It was like one of those out-there ideas that we throw around during our editorial meetings: “Wouldn’t it be cool to do a story on … ?” But this topic had my attention … especially when Chris said I should write it.

It’s not the first time the topic of growing medicinal marijuana came up—Chris gets emails once in a while from readers asking about it. Lately, we’ve even had a few new subscribers indicate that they grow medical marijuana.

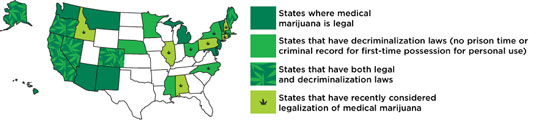

And it’s certainly in the news. Legalized medical marijuana, which was an earth-shattering law in California when it passed in 1996, is now on the docket in almost every state legislature. Currently, there are 16 states plus the District of Columbia where medical marijuana is legal (see map). Thirteen states have “decriminalization” laws (meaning no jail time for first-time possession for personal use) on the books. And as of press time, 10 other states were looking at legalization. My home state, Illinois, was one of those states considering it, but the state House of Representatives failed to pass The Compassionate Use of Medical Cannabis Pilot Program Act, deciding to place it in “postponed consideration” for now.

But despite the legalization, risks are still high. Medical marijuana growers and dispensaries have found themselves to be targets of federal law enforcement because, while legal in some states, it’s still illegal on a national level. Which means the state and local laws that make medical cannabis legal have those involved in the business walking a quasi-criminal tightrope.

But what about our industry? After all, we grow plants. And marijuana is a plant—in fact, its palmate leaf is probably one of the most recognized and iconic in horticulture, thanks to t–shirts and album covers. Should we get into growing it before the pharmaceutical or tobacco industries beat us to it, cutting us out of a moneymaking opportunity? Value-wise, according to the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), most rankings put America’s domestic marijuana crop between $10 and $25 billion annually (compare that to floriculture’s $4.13 billion). Could commercial greenhouse growers cash in on that if their businesses are in states where medical marijuana is legal? And most importantly, should they? Are there any risks for growers? Then there’s the moral issue. This is a conservative industry, after all. What might the backlash be to a story about marijuana?

After a thoughtful discussion of the possible angles and the questions growers would most want answered, we decided to dig around a bit to see if there was an opportunity for the floriculture industry in medical marijuana. If there was, we’d run the story. If not? Well, it’s back to petunias.

First, to gauge the level of controversy the topic might hold, I called the head grower of a large plug producer in California. I wanted to know if he and his colleagues ever thought about growing marijuana for local dispensaries. After all, it’s legal in California, and they already have the production capabilities and know how to handle the supplier/buyer relationship.

“It’s attractive, and I would be lying if I said we hadn’t talked about it,” my source admitted. (He asked to remain anonymous—an early indication of the sensitivity of the subject.) “In terms of us really doing it, no. This is one where we probably wouldn’t be the first mover.”

He cited the conservative nature of floriculture as a key reason.

“You have to be careful about what you talk about, even just from a political standpoint, and marijuana is one of those things that a lot of people still view as illegal, and that’s going to be a complication. Are they going to continue to place their orders and feel comfortable and safe that those orders will be shipped on time, knowing you’re growing this product? It adds risk to your organization.”

But he did go on to say that if more “legit” growers started producing medical marijuana, and they decided to as well, they’d create a totally separate company from their current business, so that if there were ever any legal issues, their existing business would be protected.

Another California-based industry professional told me she knows a lot of growers who have thought or talked about growing medical marijuana, but she didn’t know anyone who was actually doing it. And, she added, if they really did want to pursue it there are major concerns because it’s still illegal on a federal level. And, as the previous guy said, there’s the risk of damaging their reputations with their mainstream customers. “No grower would okay an interview for a national magazine article!” she said.

She was right. Lots of background but no direct sources. I was already running into roadblocks. We needed some sources who knew the topic and were willing to talk about it on the record. So Chris sent emails to a couple of his industry contacts in northern California (a center of marijuana production), to see if they knew any medical marijuana growers. I was surprised by the response. They actually gave us some names and phone numbers, and greased the skids for me by explaining whom our magazine reaches.

I didn’t get responses from a couple of them, but one in particular was extremely interested in meeting with

GrowerTalks. Jon-Michael deBettencourt has been growing marijuana for the last 12 years. He was in the process of opening a new business in Santa Rosa, California, about an hour north of San Francisco. He agreed to let me visit his operation. And he referred me to some research materials, including The History Channel’s documentary, “Marijuana: A Chronic History.” He also suggested I contact Harborside Health Center, one of the largest medical marijuana dispensaries in the country.

Okay, a trip to marijuana-growing country in northern California. Now we’ll get some answers. I asked our photographer, Mark Widhalm, to join me, for both professional and moral support. After all, this wasn’t your typical greenhouse visit; I knew I couldn’t just waltz into these facilities and ask for the nickel tour.

We flew from Chicago to San Francisco and pointed the rental car north to Santa Rosa. Our marijuana grower, Jon, called while Mark and I were deciding where to eat. He confessed that he was meeting with his attorneys and wouldn’t be able to make dinner. Hmm, attorneys? Not something you usually hear from a grower. We arranged to meet him for breakfast.

The next morning, Jon pulled up in a late-model Chevy 2500 Diesel Crew Cab. A tall, young guy with an easy smile, Jon looked like the grower of any garden-variety greenhouse or nursery crop, not someone people might label as “into marijuana.” He drove us to a local café where we could talk over eggs and coffee.

Jon comes from a military family, with some close relatives employed by the federal government. He started working for a dispensary in Petaluma, California, after high school. That’s where he learned how to grow medical cannabis (the industry prefers the proper Latin genus name over the term marijuana). Now, at 30 years old, Jon is in the process of opening his new business, a grow/dispensary operation called Emerald Empire Gardens.

When the owner of an antiquated garden center passed away last year, Jon jumped at the chance to purchase the 2.8 acres of land to start his business. In the first 10 days the property was on the market, 20 other would-be dispensary owners made an offer. Jon won out.

He first remodeled a 4,000 sq. ft. greenhouse with twin wall Lexan and re-skinned the top with the woven light-diffusing fabric (85% light transmission, 100% diffusion) from a vendor in North Dakota. A 13,500 CFM ventilation system with carbon filters and a climate controller was also included because cannabis is extremely aromatic, so the odor needs to be filtered out of an enclosed space. He installed $36,000 worth of HID lights and heated floors and began production.

Plans were in the works to tear down the remaining wooden greenhouses and replace them with two more state-of-the-art greenhouses, one for stock plants and one for production. The front of the garden center had a working koi pond, fountain and bamboo gazebo, and he intended to create a place for medical cannabis patients to relax if they wanted to use their medicine (as it’s termed in the trade) upon purchase. (This is referred to as “on-site consumption.” Not all dispensaries are licensed to do this.) He was also developing alternative healing programs, and was looking into hiring a landscape architect to develop a site plan for the old garden center area. And he planned to grow orchids and other tropical plants that the patients could purchase along with their medical cannabis.

I was jotting all of this down feverishly between bites of toast when Jon dropped a bomb. “I was in the process of getting the permits to open when we had a police intervention.”

That’s a polite way to say “raid.”

Apparently, the week prior, at 5 a.m., the new sheriff of Sonoma County and the Narcotics Task Force raided Emerald Empire Gardens, arresting the three people who live and work on the property and confiscating the contents of the greenhouse and all his equipment. At the same time, a separate group went to Jon’s house and arrested him in front of his girlfriend and her 9-year-old daughter. This was Jon’s fourth arrest for growing medical cannabis in 12 years.

I asked Jon why he didn’t say something before we made the trip to California, and he replied that his hands were tied. We had made the arrangements before the raid and he couldn’t say anything to us until he spoke with his legal council, which was just the day before.

An empty greenhouse stands

An empty greenhouse stands

after local police raided

Emerald Empire Gardens in

Santa Rosa, California. They

took everything but the heated

floors, which are rolled up in

the middle. The damage from

the “smash-and-grab” caused

the fabric roof to blow off during

a storm.

Back in Jon’s pickup, we pulled up to the gates of his business. Jon unlocked the gate and drove around back where we parked, then walked to the end of the property where the skeleton of a greenhouse stood.

“They wiped us out,” Jon said of the raid. Not only did the cops take the plants, but also the lights, the computers and even his cell phones. The damage to the greenhouse from the “smash-and-grab” operation, as Jon called it, was so severe that the roof blew off during a recent storm. Jon tried to salvage what he could.

The irony is that Jon said he’s been trying to get the new sheriff and his department to visit his operation. His attorneys even contacted the sheriff’s office to arrange a walk-through, but got no response. Instead, they decided to stake them out, he said.

“We weren’t trying to hide anything. They just came in with guns in our faces like we were drug lords,” Jon said, shaking his head. “I always try to play by the rules, but unfortunately, it doesn’t always work. What’s depressing is the amount of effort and work the team put in. It hurts.”

But with four arrests, he’s used to it. Jon estimates he’s spent approximately $250,000 total in legal fees. He has seven attorneys on retainer.

“What we’re doing is legal,” Jon says. “We’ve made a lot of headway since 1996. But there have been a lot of casualties and I’ve been one of them. But I love growing. I can’t imagine doing anything else.”

In the other cases the charges were dropped because he was arrested by local authorities—and locally, it’s legal to grow and sell medical cannabis. Once, his attorneys convinced him to plead guilty on a lesser charge and opt for probation after the federal authorities showed interest in the case. That’s when you start to worry, Jon said, and it’s why most growers who are arrested by local authorities don’t put up a fight. The more red flags you raise, the higher the risks that federal prosecutors will decide to get involved. And that usually ends with jail time.

The prospects of actually seeing real, live cannabis plants in production was starting to look bleak, because Jon wasn’t the only grower raided that week—five other medical cannabis operations were visited by local law enforcement.

Jon’s friend and co-worker Siobhan suggested we call a friend who’s fairly new to growing medical cannabis. He wasn’t included in the police raids, but because of the recent shake up, he was reluctant to talk to me or show me his crop. When I promised I wouldn’t include his name or location, he acquiesced.

It definitely wasn’t the same level of operation that Jon was building. This fellow was growing on his own property, down a steep hill. He’d recently built PVC hoop houses to create a better environment for his crop. Already a medical cannabis patient, this grower started providing plants to dispensaries three years ago when his construction business closed due to the economy.

When we visited, the plants were pretty tall—some about 2 to 3 ft.—with thick stems and bright green leaves, but they weren’t yet ready for harvest. Planted April 1, the grower said they’d be ready to harvest June 1—so it’s a fairly quick crop. Inside what used to be a shed for all of his construction equipment were two rooms: one for stock plants (mother plants, as they term them) and one where they root the clones. Once the young plants have established roots, they move them out to the new hoop houses.

This is the first year he had planted cannabis in hoop houses, so he couldn’t give me an estimate on how many pounds he might get from the 16 different varieties he was growing.

On the way back to Emerald Empire Gardens, Jon talked about the process of growing cannabis.

“It’s not worth growing outdoors,” he explained. “The [greenhouse] environment is easier to control for a better, high-quality plant, which makes up for the energy costs.” Plus, greenhouse growing takes away the “underground” stigma that comes from growing indoors or among the trees. Growing outdoors also offers a higher risk for pests—especially for a certain moth that lays its eggs on the leaves. The hatched larvae eat the buds, which could wipe out your entire crop.

Jon uses an organic media mix comprised of bat guano, earthworm droppings, chicken manure and potting soil. He buys it from a local vendor and likes it because it’s 100% organic and offers good drainage. However, he prefers to grow hydroponically if he can. “I love [hydroponic] systems and install them when I can because they’re easy to automate, no soil to move in and out, and hydroponics and CO2 enrichment go hand in hand,” he said. “We were growing in soil because of start-up costs and time sensitivity. We needed to be planted by December 21 to ensure our flowering plants would re-veg in spring.”

You have to keep the root zone warm, about 68F, which is why Jon installed in-floor heat. The greenhouse should be kept around 75-80F, and increasing the CO2 gives you a quicker crop time and 25-30% more yield.

On average, cannabis needs about 12 hours of darkness each 24-hour period to force flowering. Typically, growing indoors or in a greenhouse will give a flowering plant 12 hours of light followed by 12 hours of darkness. To grow a plant out, or what’s referred to in the cannabis world as the “vegetative cycle,” an 18-hour photoperiod followed by a 6- hour dark period will be used. Depending on the variety of cannabis grown, a flower cycle can last anywhere from 6-12 weeks to harvest. Most average at 8 weeks to harvest. Once the crop is harvested, you can either toss the plant or take cuttings to start the cycle again.

Cannabis yield is measured in pounds, with each plant yielding anywhere from ¼ to 1 pound depending on the variety, however, the larger the plant, the bigger the yield. Some large plants can yield 5 to 10 lbs. Jon said the highest grade wholesales for about $2,800 a pound. Average grade, or “outdoor herb,” sells for about $800 per pound during the peak season of September to November, and $1,200 to $1,800 off-season (late spring and summer).

Once it reaches the retail dispensary, it’s usually sold by the ounce or gram. Edibles are measured by the ounce. Think of the average marijuana cigarette (“joint”) as about 1 gram. About half a gram fits in a glass pipe.

While Jon awaits his day in court, he’s using the leftover growing media to plant vegetables for a community garden for his customers when the business opens. He hopes his full cooperation with the authorities will help his case. (At press time, the District Attorney had asked for a continuance, which means his doors have to remain closed.)

“A lot of cops think it’s a front for criminal activity, and there are people who do that,” said Jon. “They have a nasty attitude toward it, but it was voted legal. They treat us like drug lords, but everyone’s doing it.”

And that’s why Jon will be happy to see more professional commercial growers entering the medical cannabis industry. He feels it will influence state and federal officials to take notice and create laws that will force local authorities to accept it. However, he admits that the first commercial growers to take on the crop will be risking a lot. But they could be the pioneers that pave the way for others.

“If everyone was growing, how could the government keep up? What are they going to do—arrest everyone?” asked Jon. “You may have to deal with the legal aspect, but you’d be on the front lines. If you wait, you’ll be the last one in. For those who are conservative, maybe it’s not for them. But a lot of people are willing to take the risk. We need out-of-the-box thinkers to push this industry forward.”

Harborside Health Center in Oakland, which is the largest medical marijuana

Harborside Health Center in Oakland, which is the largest medical marijuana

dispensary in the U.S., resembles a cross between a bank and a jewelry store.

The center offers a wide selection of cannabis in multiple forms.

The parking lot at Harborside Health Center in Oakland was bustling with cars. Harborside is one of the largest medical cannabis dispensaries in the United States, and we were here to learn how it’s marketed.

Most legalized states have “dispensaries”—retail shops where patients can register to purchase medical marijuana products. Because dispensaries seem to come and go like traveling circuses, it’s difficult to pinpoint the total number in the United States. However, many of these retail locations are establishing themselves on a more permanent basis as the surrounding communities become more accepting of their businesses. California has 1,200. Harborside wants to be a model of professionalism among dispensaries, as opposed to the head shop image of many.

After being okay’d by a burly, but soft-spoken security guard and walking through a metal detector, I took note of my surroundings. As a frequent concert attendee, I was familiar with that sweet, earthy scent wafting out the door as we entered. In the lobby, there is a long desk, like you find at a hotel, where patients register and show the recommendation from their doctor (you cannot purchase medical cannabis without this).

The business resembles a cross between a bank and a jewelry store. Velvet ropes indicate lines where patients wait for the next staffer to assist them. Glass showcases display a wide selection of cannabis in myriad forms: dried, edible, creams, salves, oils, tinctures. There’s an area where patients can buy young plants (most legalized states allow a medical cannabis patient a limited number of plants). Patients inspect and smell the products. Their purchases are placed in non-descript brown paper bags. The facility is businesslike, the décor is simple. It’s clear that the goal is to make the patients feel safe and welcome.

Marijuana plants waiting to be

Marijuana plants waiting to be

brought out to the floor to be sold

to medical cannabis patients.

Harborside has more than 500

growers in their collective.

I already knew what Steve D’Angelo looked like because he was one of the medical cannabis supporters interviewed for The History Channel documentary I’d watched before my trip. He’s also been interviewed by The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN, The Wall Street Journal, Fortune and the BBC, so he must be a respected, qualified spokesman for the topic.

When we walked into Steve’s office, which is secured with a fingerprint identification system, a man with long, neat braids, a navy suit and a Kangol hat came from behind his desk to shake our hands and offer us a Perrier. Plaques, awards and framed articles cover the back wall, with posters from various marijuana events and demonstrations adorning the side.

Steve has been a cannabis activist for more than 40 years. In 2006, he founded Harborside, which offers more than 80,000 registered medical cannabis patients access to their “medicine” (as they term it), along with other services like counseling and holistic treatments free of charge. A second location in San Jose opened last year.

Clones Manager Jeremy Ramsay

inspects new cannabis plants for

pests and diseases. This must be

done before it can be cleared for

sale to patients.

California law states that you must be a registered medical cannabis patient to open a dispensary and grow marijuana. Both businesses also have to be not-for-profit. So how does Harborside make money?

“We make money by putting a 40% margin on all of the medicine that we take in,” Steve replied, “which basically means for every dollar that we take in, 60 cents of that goes to the grower. The other 40 cents we use to pay our rent, our payroll, our insurance, our testing program and to provide some patient services completely free of charge.”

Steve explained the “closed-loop system” that describes the supply he gets from the 500-plus growers in his network.

“We only accept medicine from people who are legally qualified medical cannabis patients and have gone through our registration and verification process, who have agreed to join our collective and obey our rules and regulations. We then limit the amount of cannabis we take from any of those patients to one pound at a time.” Steve says the tight controls and small quantities help prevent them from buying from and supporting illegal-market growers.

“You have to take steps to keep [the legal and illegal markets] separate,” he says. “There are challenges with having those two parallel markets. One of our biggest challenges here is diversion to the illegal market and making sure that people don’t buy in here and then sell it on the black market.”

Thinking of our industry’s breeding and branding capabilities, we asked Steve if there was a place in the market for patented genetics.

“I can tell you for sure that that would be met with outrage in the cannabis community,” he replied. Seeds and cuttings are freely shared between growers and dispensaries, and patients are encouraged to take cuttings from the plants, grow them out and sell their excess to local dispensaries for other patients. In the medical cannabis world, there are no propagation licenses, no royalty fees, no F1 hybrids, he says. If you’re a cannabis breeder and you’re holding a particular strain hostage, you won’t make many friends.

As there are hundreds of cannabis strains, how does Harborside choose which ones to sell? As with most retailers, supply is based on customer demand.

“That actually changes from season to season, so we see a development of a certain amount of fashion or trendiness in cannabis strains,” said Steve. “That said, one of the things that distinguishes Harborside from other dispensaries is our very wide selection. We usually have about 100 different products.”

One of the newest patient demands is for cannabis with less THC—the psychoactive component that causes the high. Steve said that, contrary to what many outsiders think, most medical cannabis patients don’t use the drug for its psychoactive effects. Instead, it’s the cannabinoid CBD that helps alleviate side effects of diseases or injuries, such as pain, nausea, appetite loss and insomnia. CBD may have curative effects as well: In recent studies on laboratory animals, CBD has shown to slow, stop and, in some cases, reverse the growth of cancer cells, said Steve. However, during the last 30 years, cannabis breeders have essentially bred out the CBD in favor of strains that have more THC. Now that there’s a legitimate medical market for cannabis, breeders are scrambling to develop new strains that offer less psychoactive effects.

I asked Steve if he’s ever been raided and was shocked when he said no. Surely a high-profile place like this would be an easy DEA target. But that’s exactly why Steve agrees to interviews: He wants to show that a medical cannabis organization can be a legitimate business. But the risks are still extremely high.

“I could qualify for a federal death penalty three times over based on the number of cannabis plants that I’ve sold, so the risks are very intense,” Steve said matter-of-factly. “It doesn’t even need to be a change in administration in Washington—all the Obama Administration would need to do is decide to change their policy regarding medical cannabis and they could prosecute me and, technically, if they convicted me, execute me. That’s as high of a stake as you can get.”

Before we left, I asked his opinion about commercial horticulture growers entering the medical cannabis world.

“We are at the point now where we’ve had a widely distributed system of cultivation, because if we had anything of large scale, the feds would come in and close it down,” Steve said. “We’re now beginning to see that open up. And as that opens up—as we’re able to put in more legal, regulated cultivation sites—we desperately need professional horticulturists, because this is something that’s been developed by amateurs, by people without training, without the benefit of modern equipment or knowledge. And we desperately need it, so I hope a lot of your readers get interested in doing this.”

Founder and Executive Director

Founder and Executive Director

of Harborside Health Center,

Steve D’Angelo has dedicated

most of his life to pro-medical

cannabis activism.

Although I interviewed a high-profile cannabis activist and two growers, I barely scratched the surface of what it takes to be a part of the medical marijuana community. Regardless of which side you’re on, it’s difficult not to be sympathetic to the plight of people who are being prosecuted for legally (at least at the state level) doing what they believe in.

Culturally, growing cannabis seems easy enough for a competent greenhouse or nursery grower, but can you make money at it? As Steve D’Angelo pointed out, the quantities purchased by dispensaries are small—a pound at a time or less. And, at least in California, you have to be a medical cannabis patient yourself to grow it. That could change as laws change, however.

And you can’t deny the obvious risks involved: raids, arrests, legal costs, high security and morality judgments from the community being just a few. And, as Jon’s 5 a.m. raid proves, the legality of production is murky. It’s still a federal crime, and even though medical cannabis may be legal in your state, how it’s regulated from county to county can vary widely.

In the end, it depends on how much of a risk taker you are, and how much you believe in the cause. In five or 10 years the risks and rewards might be clearer—but someone else may have beaten you to the business.

Laws surrounding marijuana have drastically changed since California made medical cannabis legal in 1996, with more government officials supporting the efforts of pro-legalization organizations. Based on that, don’t be surprised if you hear about one of your peers registering for a medical cannabis license within the next decade.

GT