ToBRFV-Resistant Tomatoes Introduced

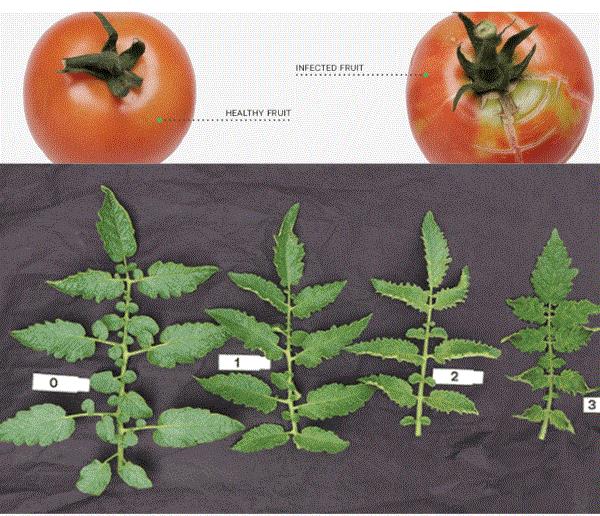

Being infected by tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) is a nightmare for greenhouse tomato growers. (The virus can also infect pepper and other solanaceous food and ornamental crops.) It was first detected in Israel and Jordan in 2015 and quickly spread to many parts of the world, likely through infected seeds because this virus is seedborne. Spread can also occur locally through mechanical transmission (such as workers handling infected plants) or pollinators. There’s also suspicion that transmission may occur via irrigation water, but this hasn’t been conclusively proven, in my opinion.

Infections have been popping up in Arizona, California, Florida, New Jersey and other places since 2019. It’s considered eradicated in the U.S. wherever the disease has been detected. Growers remain vigilant because the disease is devastating and there are very few management tools. Go HERE for an update on this disease from our own Bill Calkins.

But here’s welcome news: NRGene announced that sales of tomato seeds containing its ToBRFV resistance trait, developed in partnership with Philoseed, has begun. NRGene and Philoseed mapped ToBRFV resistance in 2022 and subsequently developed the High Resistance trait. NRGene licenses the trait to seed companies in Europe, South Africa and the U.S. for integration into these companies’ tomato lines.

Healthy and symptomatic (of tomato brown reguse fruit virus or ToBRFV) tomato fruits and leaves. (Photo credit: NRGene.)

Those who deal with viruses know that the best management is to deny them entry and establishment, either through indexed or resistant plants or early detection and crop destruction. But they’re notoriously sneaky and hard to detect.

Test kits are available from several providers. Just Google “ToBRFV test kits” and you’ll find at least six companies offering them. On the top of the list is Agdia, which I’m more familiar with (but feel free to use any other companies you already have a relationship with). Agdia offers three types of test kits for ToBRFV: AmplifyRP, ImmunoStrip and ELISA. It also has test kits for other tomato diseases, such as tomato mottle mosaic virus, begomovirus (recently introduced), Fusarium and bacterial spots.

Folks Told IR-4 What's Bugging Them

The IR-4 Environmental Horticulture (EH) Program released the results of its 2024/2025 Grower & Extension Survey ahead of its research priority setting meeting in early October. Staff and researchers who attended the meeting used the survey results to inform them which insects, mites, weeds, diseases or pest management issues are worth spending the IR-4’s precious research dollars on.

A total of 335 people participated in the survey, of which 293 (87.5%) are growers. These folks grow anything and everything, but most folks represent greenhouses and field and container nurseries. Survey respondents are roughly evenly distributed across the four U.S. regions, with very few folks participating from international locations (mainly Canada). Most survey respondents (67%) want both efficacy and crop safety data. But which pests are they dealing with?

Thrips, mites, scales, mealybugs, scarabs and aphids were ranked as the top pests when all the data was pooled. These pests also show up consistently as the Top 5 pests in most crop groups, with a few other important pests thrown in specific crop groups, such as flea beetles (particularly red headed flea beetle) in shrubs and herbaceous perennials, and Diabrotica (various rootworm species) in cut flowers.

For diseases, powdery mildew, Fusarium, Botrytis, bacterial diseases and Phytophthora took the top spots overall. Similar to insect pests, the top diseases are also featured in most crop groups. Additional important diseases are asters yellow in cut flowers, Cercospora leaf spot and nematodes in shrubs, fireblight in trees, and Pythium/Phytophthora (this option is for those who can’t separate these two pathogens) in bedding plants, foliage plants, seasonal potted plants and ornamental grasses.

Ragweed, vines, grasses, summer annual weeds and thistle are identified as overall top weeds. As expected, the top weeds vary quite a bit from crop group to crop group. Resistant ragweed, horseweed (or marestail) and lambsquarter are of great concern to many survey respondents.

I cannot cover all of the information included in the survey results summary. But trust me, I’m only scratching the surface in this newsletter. There are nuggets about which pests are important where and what IPM strategies folks are using.

Does the IR-4 Survey capture your pests, diseases and weeds of concern? No? Well, don’t miss the next survey coming up in a couple of years.

2026-2027 IR-4 Research Priorities

As I mentioned earlier, the Grower and Extension Survey results were used to help set the IR-4 EH Program’s research priorities for the next two years. But which issues are chosen for the national and regional priorities also depends on several considerations and consensus among meeting attendees. Being a top-ranked pest doesn’t necessarily mean it's a shoo-in as a priority.

The first consideration in prioritization is whether the top-ranked issues are simply very prevalent or urgently needed solutions. Unfortunately, the survey wasn’t really designed to tell this apart. For example, there was an extended discussion among attendees where powdery mildew truly deserved to be a priority. It was decided that, yes, powdery mildew is prevalent, but this disease is largely under control and has many effective management tools, so, new research isn’t needed. Therefore, powdery mildew wasn’t selected as a national priority.

But the North Central Region (which encompasses an area from North Dakota south to Kansas and east to the Ohio River) argued that powdery mildew is important for this region, particularly in outdoor nursery and cut flower production. The North Central Region selected powdery mildew as a regional priority to spend part of the money allocated to this region.

The next three considerations are whether new technologies are available for the issue, if the target pest is already registered for a new technology and if pesticide manufacturers/registrants are interested in labeling for that specific use. These are important considerations because, while the explicit goal of the IR-4 program is to bring new technology or product to pest management in specialty and horticultural crops, it’s a moot point if a priority or use is already registered or if a registrant isn’t interested in registering the pests. There was a discussion about needing new non-neonicotinoid tools for aphid management, particularly in hanging baskets. Unfortunately, most systemic insecticides are already registered against aphids and there’s no new systemic insecticides available to address this issue, so it wasn’t selected as a priority.

So, after two days of discussions (and some teasing among the entomologists, weed scientists and pathologists thrown in), here are the research priorities agreed among the IR-4 EH Program staff and researchers:

National priorities:

-

Hydrangea (species other than bigleaf) pre-emergent herbicide crop safety

-

Herbicide-resistant weed control in Christmas tree production, with a focus on early post-emergent and semi-directed application

-

Cut flower pre-emergence herbicide safety and efficacy (apply at transplant)

-

Perennial weed (thistle, bindweeds and nutsedges in particular) control in cut peony

-

Phytopythium efficacy

-

Phytophthora efficacy

-

Botrytis efficacy

-

Thrips (parvispinus, chili and western flower in particular) efficacy

-

Red-headed flea beetle (larvae) efficacy in container nursery

-

Root aphid efficacy

Regional priorities:

-

Northeast: Balsam gall midge efficacy on Christmas trees; bacterial leaf spot efficacy

-

North Central: Powdery mildew efficacy (outdoor); Lewis mite efficacy

-

Western: Symphylans efficacy; armored scale efficacy on woody ornamentals

-

Southern: Two-spot cotton leafhopper efficacy; herbicides in containerized, fruit-bearing plant (pre-sale to retail) crop safety

Go HERE to get a copy of the priorities.

By the way, there’s a plan to return the name of the Environmental Horticulture Program to its original name of the Ornamental Horticulture Program. Y’all might see that change come through the media in a few months.

Updates on Broad Mite Control

I summarized a recent GrowerTalks article by Ray Cloyd on managing broad mites in the last issue. I noted that Amblyseius andersoni and Neoseiulus californicus are used, but Amblyseius swirskii isn’t generally recommended for broad mite biological control.

Suzanne Wainwright-Evans gave me a reality check, which I truly appreciated. (That also tells me that I need to visit growers more than I do now.) Many growers use Neoseiulus cucumeris and swirskii for controlling broad mites, not andersoni, which is more expensive.

So why cucumeris and swirskii? Cucumeris is a devil we know—what it’ll feed on, how it performs against a broad range of insect and mite pests, and how compatible it is with pesticides. Most importantly, cucumeris is cheap and readily available, especially now that there are rearing facilities in the U.S. Swirskii is more expensive than cucumeris, but it’s also known for its prey range and tolerance for higher temperatures. In a way, cucumeris and swirskii are released in large numbers at acceptable costs to overwhelm any mite and insect infestation.

Janna Beckerman of Envu also texted me from her sick bed to remind me that Shuttle (acequinocyl) is registered for broad mite management.

Disease Management Course from UF

The University of Florida/IFAS Extension's Greenhouse Training Online Program will start the Practical Disease Management course on November 10. The self-paced, online course will end on December 12.

This course will be taught by Carrie Harmon of the University of Florida. You'll learn about bacterial, fungal and viral disease life cycles and favorable conditions, how to prevent disease outbreaks, organic and conventional management options, fungicide modes of action, and safe application of fungicides. Course materials will be delivered through video recordings, readings, assignments and quizzes. This is an intermediate level course that qualifies for the Plant Health Professional Certificate.

The cost of attending the course is $285 per person. A company will get 20% off if five or more employees attend. Go HERE to find out more about the course or to register.

Pretty Useful Wasp

My good deed last week was to rescue a wasp from a water trough at a horse farm on Wadmalaw Island, South Carolina, where my daughter works at. (With my daughter in charge, I'm afraid the farm will turn into a shelter for all unwanted animals within a year. In addition to horses that actually pay their room and board, newly adopted and came free are two ponies, a miniature donkey, three goats and three kittens.) The red-and-black wasp recovered quite quickly after it was fished out of the water and placed on a fence post.

Having good karma smile upon me is one reason for the rescue. (I still haven’t seen what karma brings, actually.) There’s another reason—I recognized the wasp as Larra bicolor, which has a very distinctive black head and thorax and red abdomen.

I usually can’t tell one wasp species from another, but this one? I know it because we have a history. If I hadn’t joined the floricultural entomology program of the late Dr. Ron Oetting at the University of Georgia, I’d have probably studied this wasp under the late Dr. Howard Frank at the University of Florida. Also, I was the turf and ornamental entomologist at Clemson University when this wasp was found in South Carolina.

Larra bicolor was first introduced from South America to Florida to control the invasive tawny and southern mole crickets. It spread on its own, probably followed the trails of its two host species, and can now be found from Texas to the Carolinas.

Larra bicolor is a biological control agent of the introduced tawny and southern mole crickets, but it doesn’t attack the native northern mole cricket. Different from what we typically think of parasitoids, which have larvae growing inside the hosts, Larra bicolor is an external parasitoid or ectoparasitoid. The larvae latch on to the hosts on the outside and suck the hosts’ “blood” dry. The larvae then pupate happily next to the disintegrated bodies of their hosts. Each generation can kill about 25% of mole crickets in an area and there are three generations per year in Florida, so its effect on the mole cricket population adds up.

Go HERE for a wonderful article by Howard Frank and Andrei Sourakov of the Florida Museum of Natural History. This article has a series of pictures illustrating the interactions between Larra bicolor and its mole cricket host.

Great to have lent a hand to a pretty and useful wasp.

That’s all the news and updates for this week. I’m going to get away from the computer and go out there to see how pests are managed.

See y'all later!

JC Chong

Technical Development Manager at SePRO

Adjunct Professor at Clemson University

This e-mail received by 27,847 subscribers like you!

If you're interested in advertising on PestTalks contact Kim Brown ASAP!